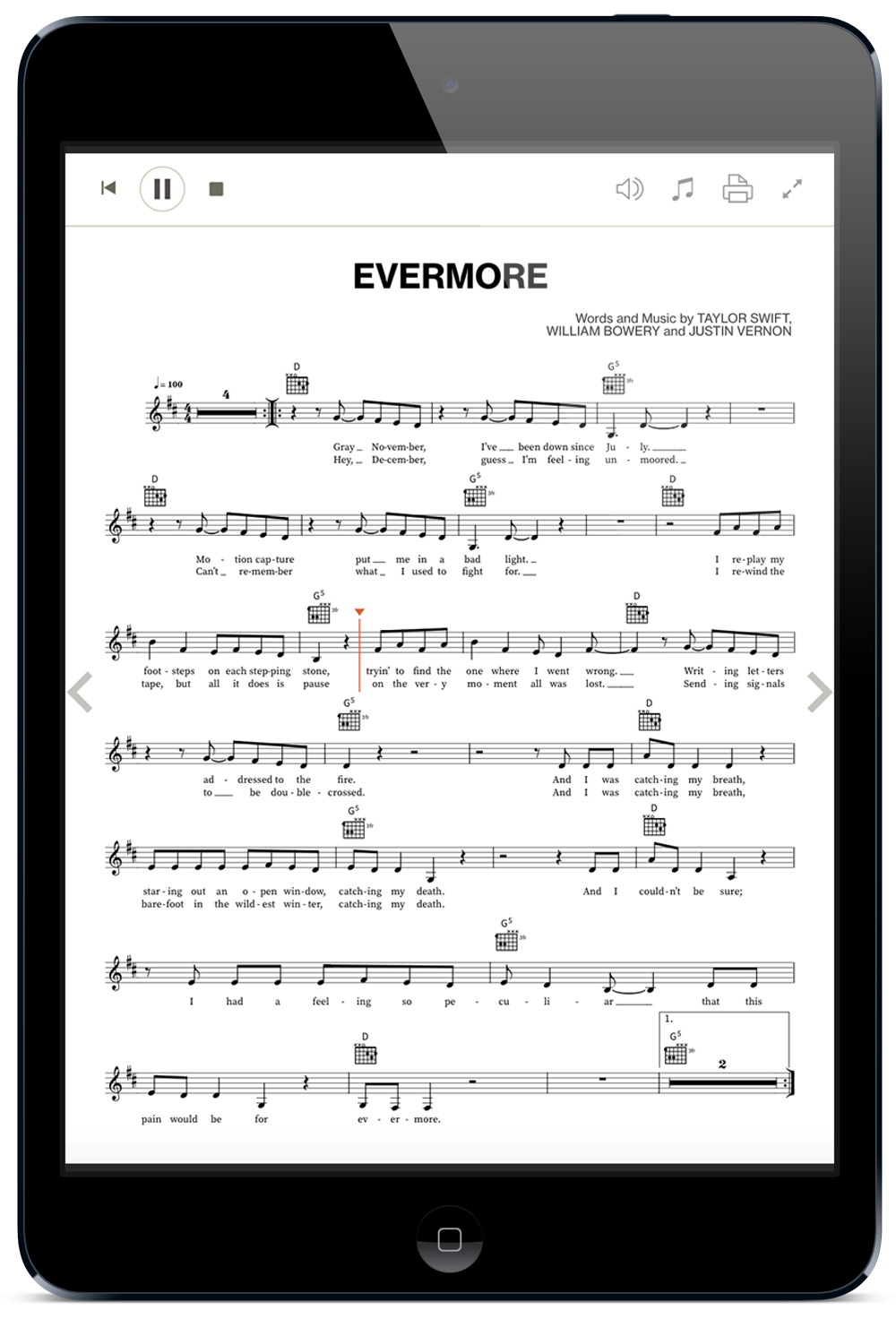

Hal Leonard has made sheet music for songs such as Taylor Swift’s “Evermore” interactive at retail.

Print music is not an instrument, it’s not an amp, it’s not an accessory, it’s not even just a piece of paper. It’s intellectual property. As such, the internet can contort its position in the market in many ways.

But one thing is clear. For the last 15 months, it’s been hard to sell.

George Quinlan Jr., CEO of Chicago, Indiana and Michigan-based retailer Quinlan & Fabish, broke it down. “Any music that was related to an ensemble, like concert band, marching band and jazz band, orchestra, anything, was down somewhere in the neighborhood of 80 percent,” he said. He did identify some bright spots though. “What happened is that as schools started teaching virtually, they could no longer perform in an ensemble very easily online,” Quinlan said. “So they went back to the basics and started reviewing “Essential Elements” or whatever method they were using because it was easier to teach those things online than it would be to teach an arrangement of a concert band piece.” Asked to name his best seller over the last year, Quinlan guessed it’d be Hal Leonard’s “Essential Elements Book 1 Clarinet.”

Some things at Quinlan & Fabish remained the same in pandemic. “We only really have two types of customers: The teachers themselves, and then those students that they recommend to get this book or whatever,” Quinlan said. “It really didn’t change their habits in the sense that [teachers] would call up an order and then we would bring them out to the school. But we don’t have as much retail [from] parents ordering

books individually.”

So, Quinlan & Fabish made a deliberate effort to reach students themselves. “Our reps did a lot of house calls, because the kids needed their books or their instruments fixed or whatever,” he said. “We called it QPS.”

The company felt this was necessary because it wanted to help make sure students stayed in school music programs. “Retention has been challenged at every level,” Quinlan said. “Usually by the time kids get to eighth or ninth grade, they’re committed. They’re not going anywhere through 12th grade, but we’ve talked to a lot of high school teachers that have experienced some attrition — kids that just got discouraged with the whole challenge of trying to learn an instrument and they’re missing the social parts of music participation, the performance parts. Those are the most exciting parts.”

Eric Strouse, president of Stanton’s Sheet Music in Columbus, Ohio, is another retailer in the space who has seen challenges over the last year. “My largest department is my choral department, and that went from tens of thousands of dollars a month to nothing,” he said. He cites a program called SharedWork Ohio as having saved the store. Basically, this program allows a business’ staff to go on reduced hours and unemployment with no expectation that they look for work, with the plan being they’ll be taken back full-time at some point. Strouse said that without this, “I would’ve shut my doors. I couldn’t make payroll, let alone pay

my vendors.”

Some, of course, went that route, which Strouse finds short-sighted. “When I spoke with some of my friends around the business, they were just letting their employees go — long-term employees, guys who’ve been there 20, 30 years,” he said. “I was like, ‘I’m going to need these people next year. I can’t re-train experience like that.’”

One thing the coronavirus did for sheet music is force anyone shy about downloading it to just do it. “A lot of the teachers that were apprehensive about doing digital downloads back then are now comfortable with it,” Strouse said. “So I think this next year we’re going to have a huge surge in digital downloading. I was probably double my sales in

that category.”

But this only goes so far. “I love it, but to be honest with you man, it still only represents like one, maybe two percent of the business, and the rest is sheet music,” he said.

Don Langlie, owner of Popplers Music in Grand Forks, North Dakota, is another MI retailer who does heavy business in choral and confirms Strouse’s assessment of the effect of the pandemic here, terming it “brutal.” But what sold well for him over the last year is somewhat fun — classic rock songbooks. “It was probably some nostalgia for the ’60s and ’70s,” he said. “I think it was older people [who] were stuck at home, just from an older generation that was more cautious about going out and had more time on their hands.”

It’s startling to see how slowly the multimedia paired with sheet music and songbooks is changing. “Individuals are coming to expect a digital download versus a physical CD,” Langlie said. “It’s absolutely moving that direction.” This is as people listening to music were seemingly done with CDs 15 years ago and even MP3s now seem passé.

Still, at the school level, Langlie, as Stouse did, saw improvement in technological prowess, and cites an assist from publishers here. “The flexibility of many publishers to allow the sharing of their materials digitally with their students, some flexibility in the copyright law aided in that and it was important,” he said. “It made that more workable.”

John Mlynczak, who has just been promoted to vice president of music education and technology at music publisher Hal Leonard, can speak directly to this. “As soon as the music room turned into music Zoom, we started getting a flood of rights requests from those that wanted to do the right thing,” he said. “And of course we recognize that there’s a lot print music out there that says you can not visually reproduce this at all. That’s sort of print music legacy.”

Admirably, Hal Leonard swung into action. “We worked very quickly last March to provide guidance and try to be as flexible as possible to understand that at a high level, if the teacher-classroom relationship is the same, except recreated digitally, we want teachers to know that music they’ve purchased to use in class can be used in a virtual class, as long as they take every precaution to protect that music from being distributed beyond that class,” Mlynczak said.

Evermore (Your Version)

If parts of the sheet music industry are adverse to technology or adopting it slowly, it still seems to be sweeping the market and the pandemic accelerated that. Quinlan made that plainly clear. “It seems like those publishers that had that technology embedded into their products had a distinct advantage during the pandemic because all those things were needed,” he said. “Teachers are creatures of habit like anybody else. A lot of times they just like a particular book, but the ones that had technology features built in seemed to have a

big advantage.”

Recognizing this, Hal Leonard is building a lot of technology into its offerings, and has been for a decade. “Starting back in 2011, we launched an interactive music viewer that is available through retailers,” Mlynczak said. “That program has been awhile around for a while, but behaviors are showing us that people really want to interact with

their music.”

Mlynczak explained how this serves retailers and their customers. “Brick-and-mortar retailers can subscribe to an in-store program, where if a customer walks into the store and goes to the sales associate and says, ‘Hey, I need Taylor Swift’s ‘Evermore’ but I need it in D-flat,’ they can go and they can access our portal directly, pull up that piece, and that retailer can sell it to the customer and interact with it, and print it out right there on demand.”

Hal Leonard is moving songbooks to market faster than ever before. For example, Taylor Swift surprise released her album Evermore on December 11, 2020. Hal Leonard had the “Evermore Piano/Vocal/Guitar Songbook” available by January 1 (appropriately, New Year’s Day, an occasion Swift once dedicated a song to). Mlynczak explained why such swiftness in transcribing and releasing an album’s songbook is essential.

“As soon as a musician can hear the album, there’s the lyrics and the chords on the internet illegally,” he said. “We’re committed to increasing our speed because we, of course, have the rights to publish this music and a lot of these things that go up online are not the most accurate. We want the official, approved, accurate, publisher edition out to consumers as fast as possible. And we want to build that trust and we hope that the music industry and the musicians using the music will respect and understand that we, as a publisher, are working for the artists whose music they love.”

One place unauthorized transcriptions of popular music pop up is YouTube. Heath Mathews, senior vice president of content and licensing for music publisher Alfred Music, weighed in on how this and illegal transcriptions in general affect the print music industry. “Open platforms like YouTube undoubtedly have an effect on certain aspects of the print music industry,” Mathews said in speaking to Music Inc. via email. “Illegal and infringing sites have also been a drain on legitimate methods for accessing content. However, similar to the shift that occurred in the music and video industries, the sheet music market is evolving to a model where easy access to a wide range of content is key. As content creators, our role is to find the best method to provide customers access to the long tail of content, while also making sure that our retail partners have easy access to our best sellers.”

But sheet music retailers are not so sure that YouTube competes with them. “People who watch those guitar instruction videos to learn how to play ‘Eruption’ from Van Halen, they’re not looking for the Van Halen book,” Strouse said. “They don’t read sheet music, and they don’t necessarily need sheet music when they can just drop a needle or learn off of a video.”

Langlie dismissed YouTube as competition as well, but admitted it may be

an unknown.

“I don’t see it necessarily as related, but it’s a little hard to tell because you don’t know what you didn’t sell,”

he said. MI